As hunters around the country draw nearer to their respective hunting seasons, it’s inevitable that we refocus on our hunting regions and conservation issues. Chronic wasting disease (CWD) is a term many hunters are vaguely familiar with, but how much do you actually know about the disease and its spread throughout the U.S.?

What Is CWD?

A neurodegenerative disease resulting in abnormal behavior, loss of body condition, and eventual death, CWD is a prion disease with a non-living disease vector (the infamous “Mad Cow Disease” is bovine spongiform encephalopathy, another prion disease). Prions are an abnormal form of a typically harmless protein found in the brain and are responsible for a variety of neurodegenerative diseases in both animals and humans.

These diseases occur when normal protein folds and “clumps” in the brain, causing brain damage. Scientists are still uncertain what causes the clumping, and the disease is almost impossible to test for in living animals; many diseased cervids (members of the deer family) may show no signs of the disease for several years yet still actively be spreading CWD.

How Is CWD Spread?

Transmission of CWD is thought to be lateral—passed from animal to animal, not from mother to fetus—and can occur through direct contact via saliva, blood, urine, and feces, or indirectly through the environment: water, food, and even the soil.

What Are CWD Symptoms?

Visible CWD symptoms generally include weight loss, a drooping head, and salivation. The National Deer Association (NDA) notes that most hunters will never see a deer showing classic symptoms of CWD, as animals typically die from a variety of indirect causes before exhibiting evidence of the disease.

Where Has CWD Been Detected?

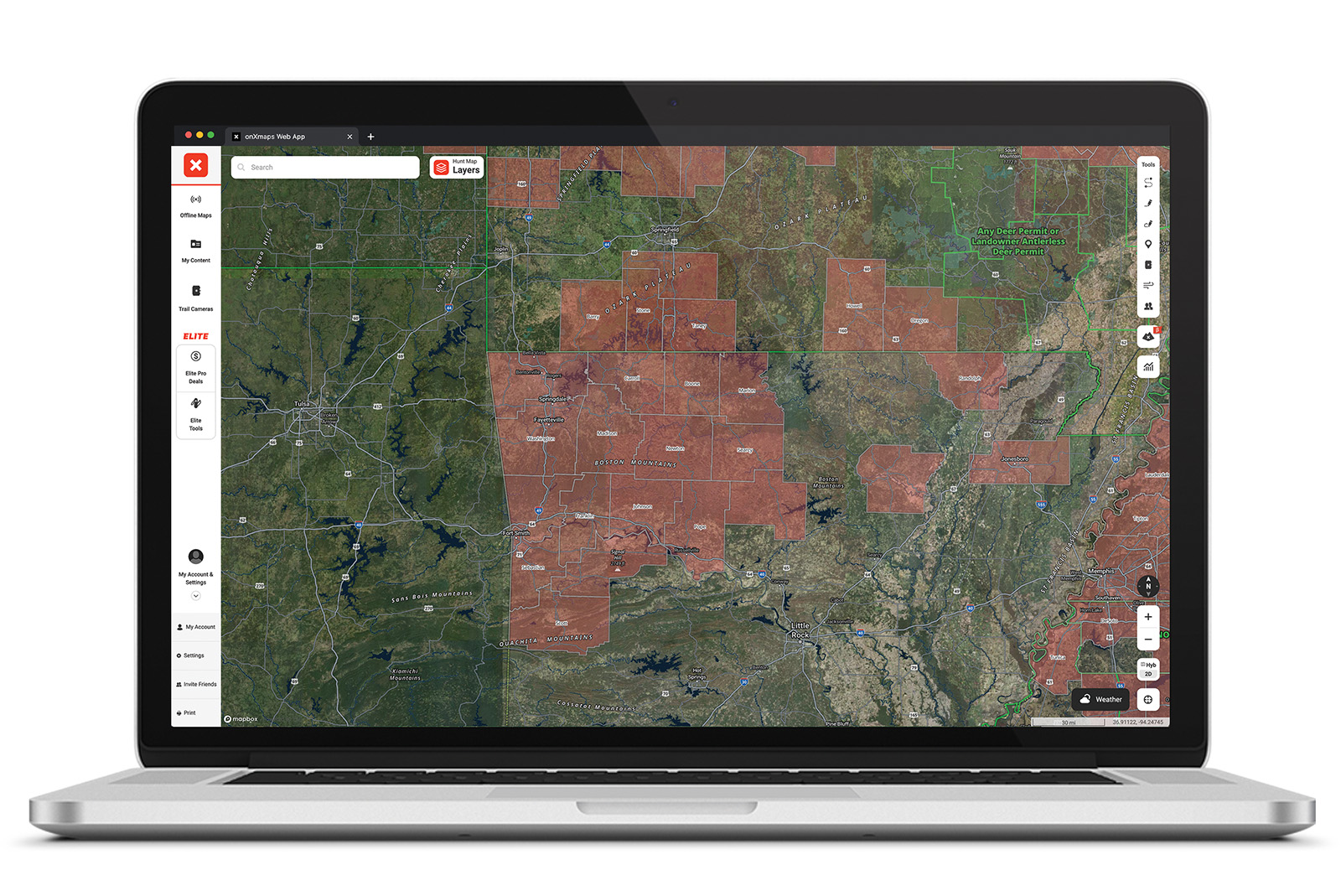

CWD has been identified in 36 states and continues to spread (see expandable list below). The Hunt App’s CWD Map Layers show you a county-by-county breakdown of CWD distribution. Create an account for a free 7-day trial and review CWD areas, regulations, testing locations, and carcass disposal sites.

States With CWD (as of May 2025)

Alabama

Arkansas

California

Colorado

Florida

Georgia

Idaho

Illinois

Indiana

Iowa

Kansas

Kentucky

Louisiana

Maryland

Michigan

Minnesota

Mississippi

Missouri

Montana

Nebraska

New Mexico

New York

North Carolina

North Dakota

Ohio

Oklahoma

Pennsylvania

South Dakota

Tennessee

Texas

Utah

Virginia

Washington

West Virginia

Wisconsin

Wyoming

Can Humans Get CWD?

When asked about the possibility of CWD in humans, Dr. Krysten Schuler, Wildlife Disease Ecologist in the Animal Health Diagnostic Center at Cornell University, noted, “I don’t think we should just write it off and say it’s not a possibility. I’m a prevention person. There are possibilities where we would be worried about it.”

No one is certain how the disease would manifest in humans, and some scientists speculate cases could be present that have not yet been identified as linked to CWD.

For his part, Dr. Fischer is a hunter living in a known CWD area. He actively hunts, and does consume deer meat from CWD areas, but only after it has tested negative for the disease.

CWD Management

So what does CWD management look like? Dr. Jonathan Mawdsley, Science Advisor for the Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies, notes that currently, “CWD response belongs to the states.” Federal aid would be helpful, certainly, but is not likely to occur in the near future. States need increased funding for research and testing—resources are fairly minimal currently, and the number of labs that can run the required testing is limited. State wildlife agencies are able to direct hunters to the best lab for testing.

There are biological, economic, and social sides to the disease, and there is no easy answer. State wildlife agencies will always draw contention but often work to create management tactics that work for hunters, not to hunters—the long-term good of the resource and the sportsman is continually considered. Many states with CWD are not seeing a subsequent decrease in hunting license sales; Wyoming, for example, is seeing as much as a 20% uptick in license sales in the past few years, notes Scott Talbott, the Director of the Wyoming Game and Fish Department.

Once established in an area, CWD looks like it’s going to be there, surviving in the deer, the water—even the soil itself. The most effective way to manage is containment—to never let the disease beyond the areas where it exists already. Avoiding the transportation of diseased game will go a long way in this prevention, and in some areas, it’s the law.

“The need to keep it out of areas where it’s not is the most effective way to manage it,” commented Matt Dunfee, the Director of Special Programs for the Wildlife Management Institute and CWD Alliance.

Hunting in a CWD-Positive Region

So what does this mean for hunters, and how do we prevent its continued transmission? Dr. John Fischer, Director and Professor at the Southeastern Cooperative Wildlife Disease Study, College of Veterinary Medicine, The University of Georgia, boils it down simply: “Prevention is the only truly effective method for managing chronic diseases in wild populations. Period.”

Hunting in a CWD-positive region should change hunter behavior, and hunters should keep the following considerations in mind, in addition to understanding any CWD-specific regulations in the books.

Breaking Down a Deer

When breaking down a deer, bone out the animal, taking extra care around the high-risk tissues where CWD prions accumulate: eyes, neck lymph nodes, brain, tonsils, backbone, intestinal tract, and spleen.

Transporting Deer

Avoid transporting whole, intact animal carcasses and trophy heads from CWD-positive areas. Increasingly, specific regulations govern the transportation of deer, so be sure to review state-specific rules before your hunt.

Hunters in non-CWD areas can hunt responsibly when traveling in CWD areas—process your animals appropriately and move the meat responsibly. Remember even a seemingly healthy deer can test positive for CWD.

Carcass Disposal

Bag the carcass and dispose of it at a designated carcass disposal site (the Hunt App shows you where these are). Burning, rendering, or composting carcasses will not break down infectious CWD prions. Hunters should take these precautions even if the deer they’ve harvested from a known CWD area looks healthy—animals can be infectious while still outwardly appearing healthy and normal.

Testing for CWD

Test your game for CWD and wait for the results before eating. There are a limited number of labs that can run the correct tests, so this could mean a waiting period of up to several weeks for results, but it is important to have the test results in hand before meat consumption. The Hunt App’s CWD Map Layers show you where the nearest sampling location is.

And remember to test more than just your deer: CWD is found in most cervids, including elk, moose, mule, and white-tail deer—and is 100% fatal to all deer species.

The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) is actively looking for the disease in humans (and has been for several years) and to date, there have been no known cases of CWD in humans, but their official statement is “no consumption of CWD-positive meat.”

Other Considerations

Hunters should also consider alternatives to natural deer urine-based lures, and report any odd deer behavior to state wildlife agencies.

header image: Sam Soholt