Ducks and Wetland Conservation in Memphis, Tennessee

In a place known for barbecue, blues, and Beale Street, local conservationists are working on another accolade—public wetlands.

Memphis sits at a crossroads. Economically, its position along the Mississippi River and Interstates 40 and 55 draw mega-employers like Fedex, Autozone, and International Paper. Culturally, the home of St. Jude’s Children’s Hospital, Elvis, and the blues, boasts some of the country’s richest history as well as some of its most troubled present.

These ebbs and flows of prosperity have left sharp lines between the haves and the have-nots. Travel through the park at Mud Island and you’ll see homes valued at nearly $1 million, while just over the bridge lie neighborhoods wrecked by poverty. Gentrification has played a part in the history, and continues to influence the future of Memphis. Yet, the rivers that define the landscape pay no mind to the neighborhood they flow through. While the Mississippi River is the behemoth that is rightly credited with commerce and economy, another Memphis waterway caught the attention of onX—the Wolf River.

The Wolf River

It begins at Baker’s Pond in the Holly Springs National Forest in northern Mississippi. It flows west through rural communities such as La Grange and Moscow, then into the fast-growing suburbs like Collierville, before its confluence with the Mississippi at Mud Island, 105 miles from its headwaters. As you approach the urban reach of Memphis, the river takes on a slightly less-than-aesthetic appearance. Its banks are littered with tires—like, an incomprehensible amount of tires—household trash, discarded toilets, and mattresses. It has been a dumping ground.

The onX Adventure Forever Grant

Drive along the city streets, and you’ll still see trash and debris from human-caused degradation, but if you look a little closer with an eye toward access and restoration, you will see the good work of Memphis-based land trust, the Wolf River Conservancy. Since 1985, the land trust has been acquiring land for conservation, cleaning up the waterway, and educating Memphians about its importance. They’ve put about 20,000 acres into conservation along the Wolf River, with about 15,000 available for public hunting.

In 2023, they applied for an onX Adventure Forever Grant that would aid them in purchasing an 86-acre parcel, intending to clean it up and open it for public hunting and fishing. The grant parcel is an area four miles north of Beale Street. “It’s part of a larger vision for that area to create a public asset five minutes from downtown. It will become public hunting and fishing land, either administered by Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency (TWRA), or the pie in the sky, make it a national wildlife refuge,” says Ryan Hall, Director of Land Conservation for the Conservancy. What makes it so special is the proximity to a population source. According to Hall, over 100,000 people live within a 10-minute drive of this parcel which will provide a close-range opportunity for Memphians to recreate. The accessibility is hard to beat and helps provide opportunities with fewer barriers for folks new to these pursuits or experts looking for a close-to-home option.

The Catalyst

The Wolf River Conservancy is dedicated to the preservation and enhancement of the Wolf River and its riparian ecosystems. One of the primary goals of the Wolf River Conservancy is to maintain and expand public access to the river through the creation and management of trails and recreational areas. The Conservancy has been instrumental in developing the Wolf River Greenway—a multi-use path for hiking, biking, and birdwatching. This path, and the conserved property around it, enhances the ecological health of the river corridor by linking fragmented habitats that are common in Memphis.

The lands they manage face a few key threats. “Illegal dumping is a huge issue. Private and public property—the dumper does not discriminate,” Hall says. The second one is illegal off-road usage near wetlands. Two-track roads and pirate trails can be seen off any highway, particularly under powerlines, but near wetlands, these can be incredibly damaging. The third is nothing unique to Memphis and can be seen across the country’s wetlands—real estate development. “It’s relatively easy to develop in the floodplain in Tennessee, and that means filling-in of wetlands,” Hall says. That’s incredibly devastating for waterfowl populations and adds urgency to the work of the Conservancy.

Yet, amidst all these challenges, Hall finds encouragement that as more public access is created, the good users of the land are keeping the bad actors at bay. “By activating the Greenway through these areas, you’re cleaning it up, getting more eyes on it, and getting more recreational users that appreciate it,” he says. The public land users are taking responsibility for the stewardship of the landscape.

Public Hunting Access in Memphis

The work of the Conservancy is critical to accessing the area’s public lands. Despite Memphis’ notoriety as a gateway to the Mississippi Flyway, accessing those ducks is a challenge for public land waterfowlers. “I’ll either wake up at one or two in the morning to drive somewhere way outside of town, or sleep in my truck at a trailhead to hunt in the morning,” says 23-year-old dedicated Memphis waterfowl hunter, Roman Rushing. While areas like Meeman-Shelby Forest State Park and the Wolf River WMA (a project of the Wolf River Conservancy), create access—pressure is fierce.

Private hunting land is plentiful, but leases are steep. “We’re in a fairly lease-driven part of the country,” says Darin Blunck, the chief financial officer of Memphis-based Ducks Unlimited and Board Member of the Wolf River Conservancy. The international scale of Ducks Unlimited allows Blunck to think intra-continentally about waterfowl and wetland preservation. Still, he shares that boots-on-ground partners provide an incredible resource to get the work done. “The Wolf River Conservancy, our local partner here in Memphis, has been focused on expanding public access for many years,” he says. Both organizations are dedicated to putting wetlands habitat on the ground around Memphis so that Rushing, and others like him, can experience the satisfaction of conservation. This means that local hunting access can beget more public land advocates.

The Mississippi Flyway

The Mississippi Flyway is one of four major migratory routes waterfowl use in North America. It extends from the Arctic and sub-Arctic regions of Canada and the northern United States down through the central United States, including the Memphis area, and into Mexico.

Strategic Location: Memphis lies near the midpoint of the Mississippi Flyway, making it a prime location for duck hunting. The city’s location along the Mississippi River and its proximity to extensive wetlands and bottomland forests provide critical stopover points for migrating ducks and other waterfowl.

Wetland Habitats: The diverse wetland habitats around Memphis offer essential resting and feeding grounds for migratory birds. Estimates suggest that Tennessee has 787,000 acres of wetland habitat across the state, yet much of it exists in the southwestern region—Memphis and surrounding areas.

The Cleanest Water in the Country

These wetland habitats around Memphis serve a greater purpose than a haven for waterfowl—they’re also a filter for the Memphis Sands Aquifer. It’s some of the cleanest drinking water in the country, and the community has rallied around it. “People know that their drinking water is good,” Hall says. The system is complex, but wetland conservation is a key component of a clean aquifer. Signs around Memphis are plentiful, proclaiming “Protect Our Aquifer.” Often, what they’re fighting are real estate developments that threaten wetlands. “We get heated about it. It’s our drinking water and we should have a say. If it doesn’t rain a day in the next 10 years, we’d still have clean drinking water,” Hall says. This protection of the aquifer is not only good for drinking water, but it’s also good for duck hunters, anglers, and people who enjoy public access.

The Future Of Public Wetlands Depends on Us

The future of recreation and public land access looks strong in the Midsouth. With strong tradition, passionate conservationists, and the right access, Memphis can continue to provide high-quality wetland habitat for its citizens and visitors. The community needs that access and organizations like the Wolf River Conservancy to create more stewards.

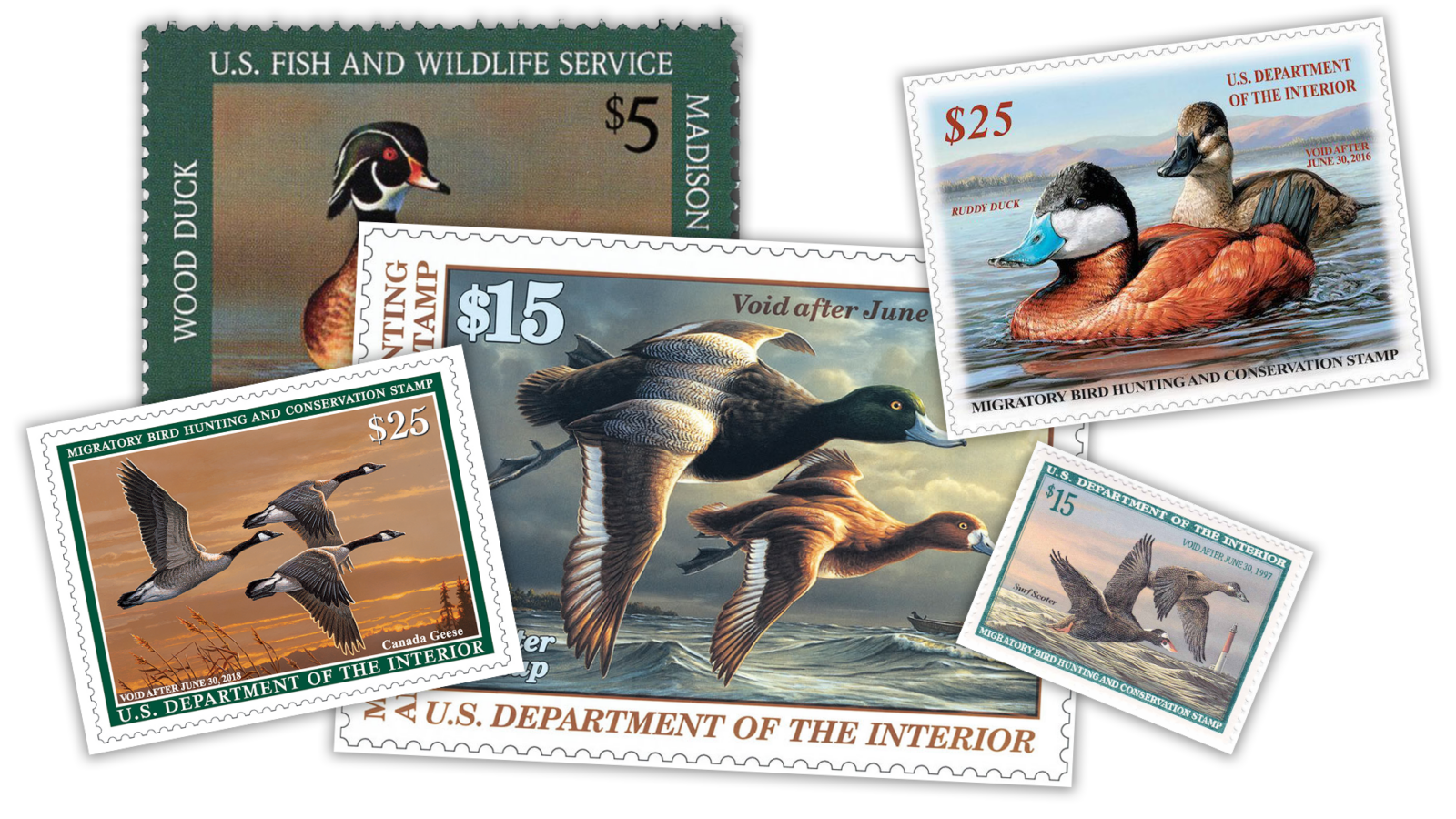

What can you do to support wetlands? Buy duck stamps, not just one, but two or three. National wildlife refuges that support waterfowl habitat are inextricably linked to duck stamp funding. So whether you’re a hunter, bird-watcher, or simply understand the importance of clean water, buying a duck stamp gets us one step closer to healthier populations and ecosystems. Secondly, get involved in your local land trust. Find one in your area; you’ve probably recreated on one of their parcels already. And support the large groups, like Ducks Unlimited, who have a seat at the table in important conversations around the continent.

If you’d like to visit Memphis, or perhaps do a public land hunt nearby, visit the Wolf River WMA and Ghost River State Natural Area. These have been keystone projects of the Wolf River Conservancy and provide opportunities in unique landscapes.