The Corner-Locked Report

Controversial Corners Restrict Access to 8.3 Million Acres in 11 Western States: We wanted to get the hard facts on corner-crossing, so we dove into the data. Read the report to learn how much land is involved, the concerns of affected property owners, and what can be done to address this complicated issue.

Controversial Corners Restrict Access to 8.3 Million Acres in 11 Western States: We wanted to get the hard facts on corner-crossing, so we dove into the data. Read the report to learn how much land is involved, the concerns of affected property owners, and what can be done to address this complicated issue.

March 2025 Update: The Report below was written in April 2022 and remains a timestamped source of information. As of March 2025, the 10th Circuit court ruled in favor of a group of hunters, who had “corner crossed” from one section of federal land to another in Wyoming, passing over a property corner shared with two parcels of private land. Until this court ruling, corner crossing existed in a “legal gray area,” and while this is a step forward for access, the nuance is real and the caveats are important. Read our new post to learn more.

Overview

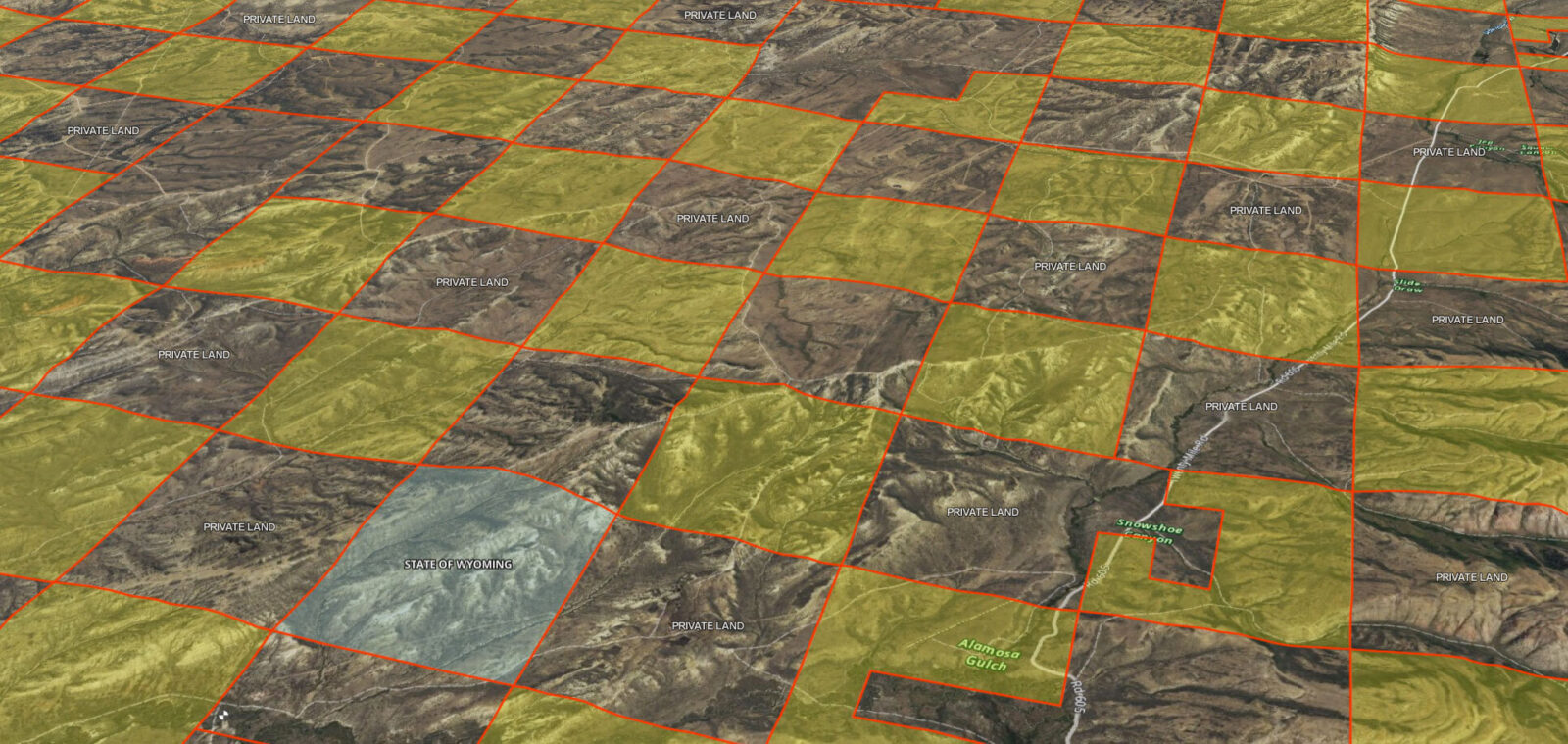

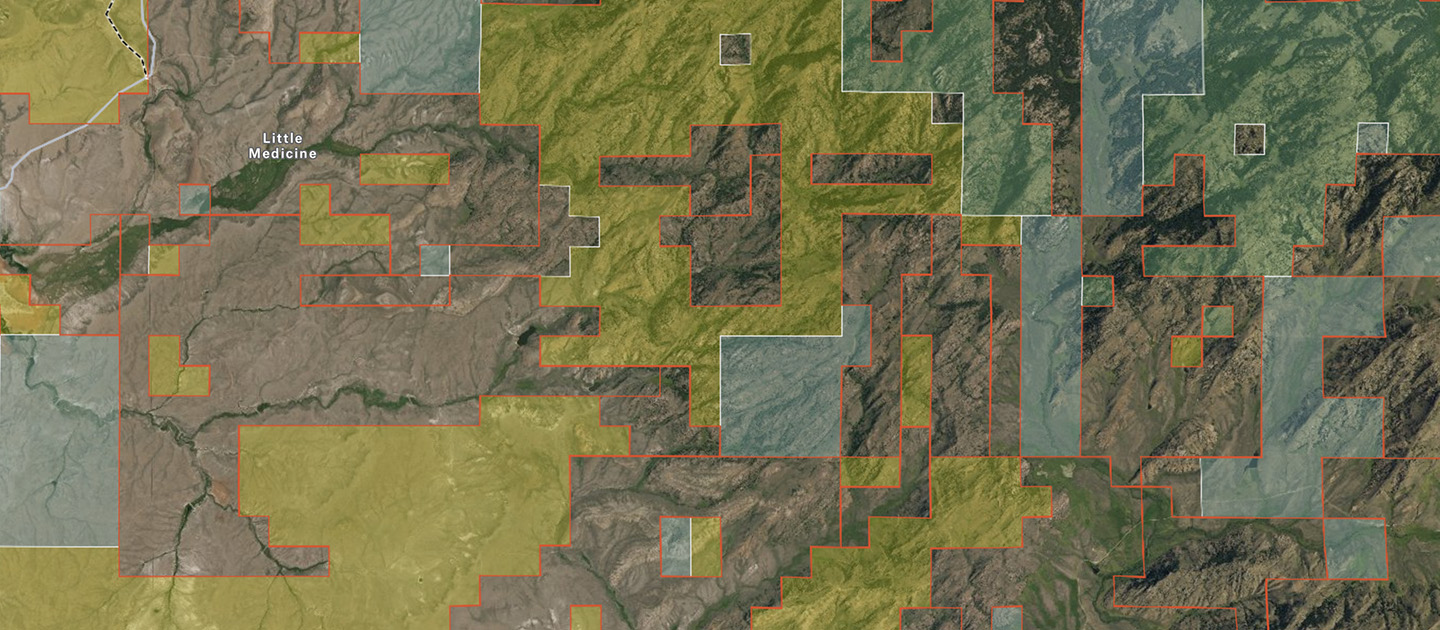

Over the past two centuries, legislation, random chance, and a variety of land deals have left the American West with a patchwork landscape of public and private land. Within the patchwork lie swaths of alternating sections of public and private land, like the squares of a checkerboard. At every point where four squares meet, there is a property corner ripe for controversy. With the issue of corner-crossing in the news again, we decided to leverage our strengths and drill down on the data. What we discovered was shocking in its scope.

The Highlights

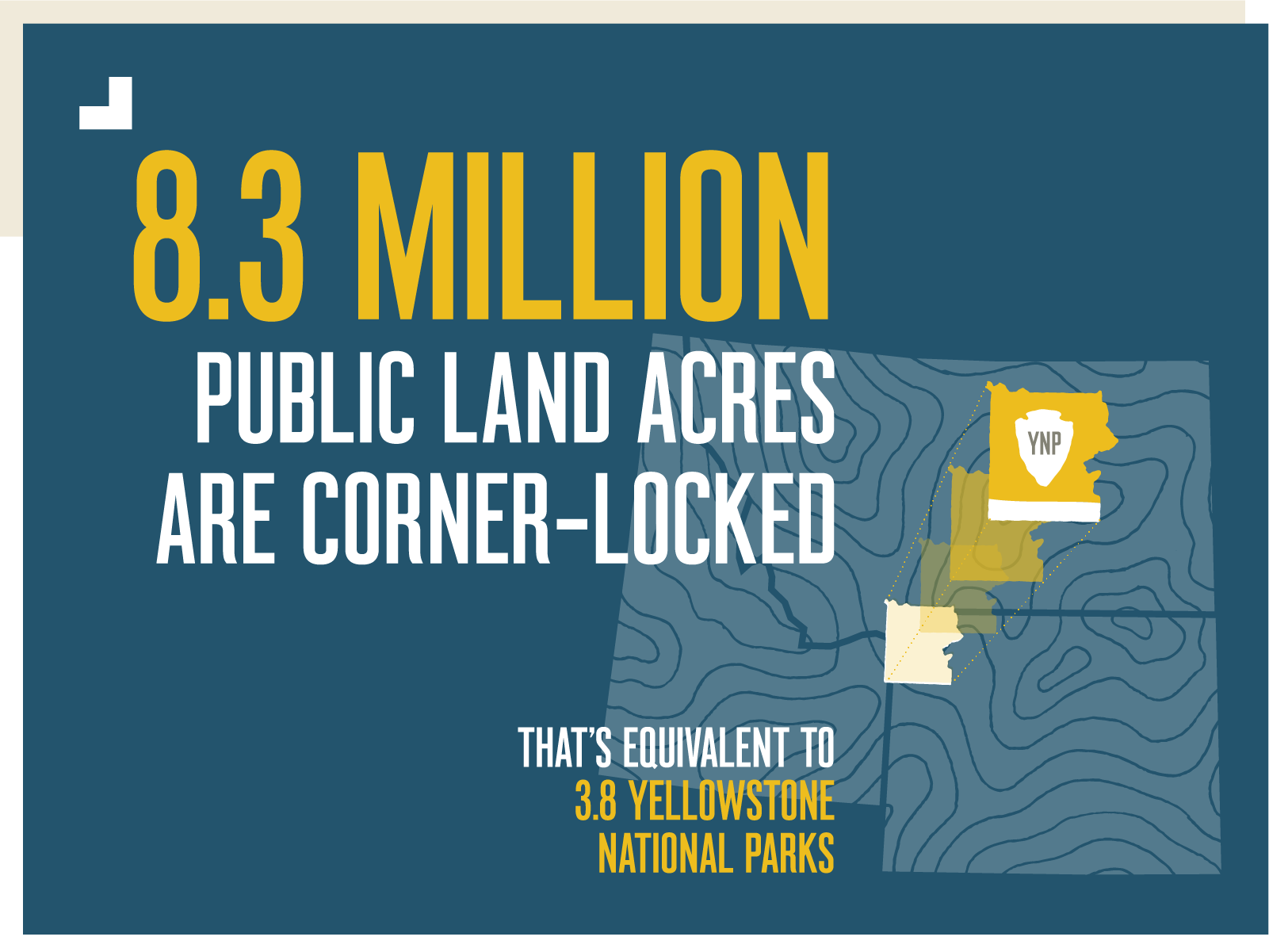

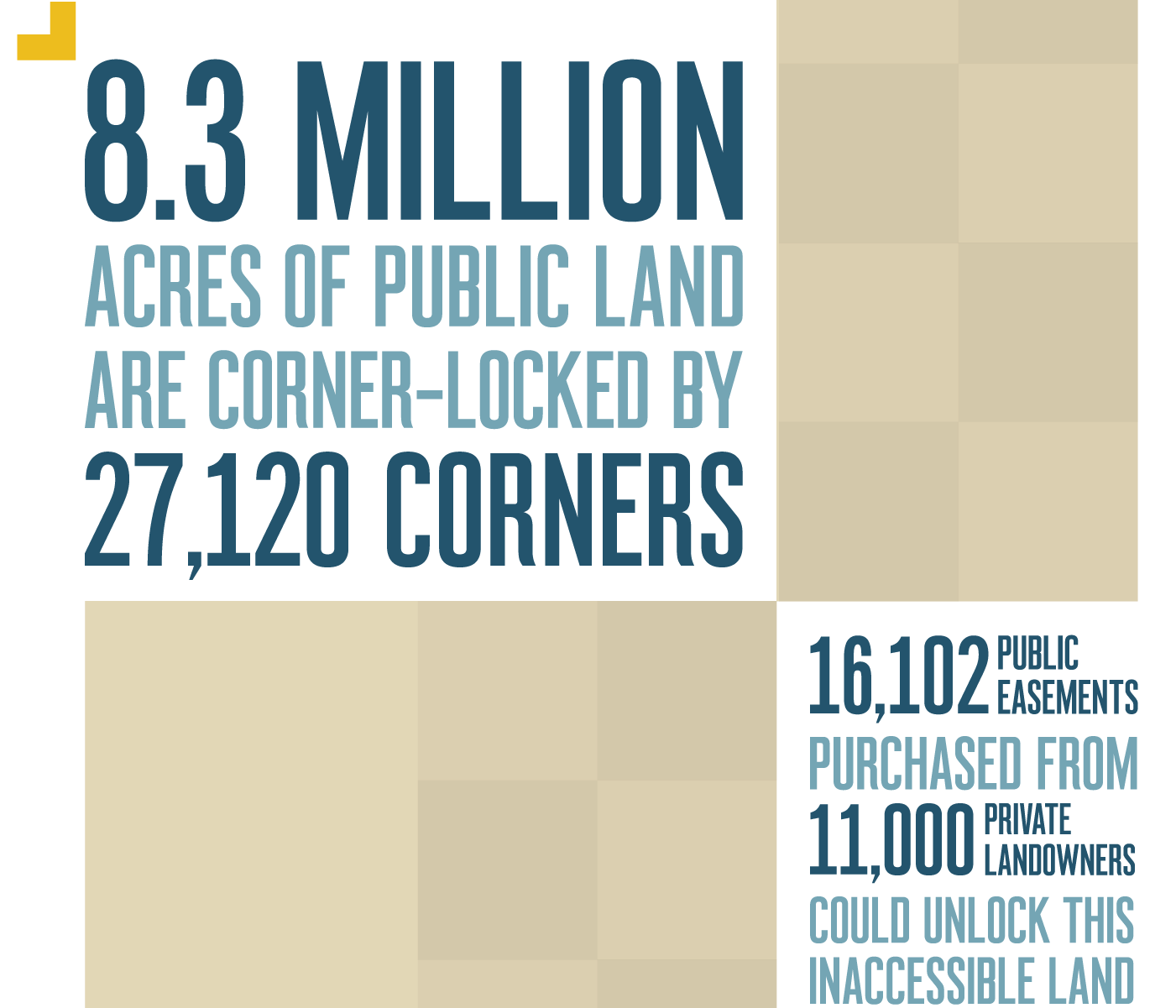

- Using our onX mapping technology, we identified 8.3 million acres of corner-locked lands—more than half of the West’s total landlocked area.

- 27,120 land-locking corners exist in the West.

- No law exists that specifically outlaws corner-crossing, but various attempts to make it either definitively legal or illegal have thus far failed.

- Property owners have valid concerns, and any solution to the problem must address landowner needs.

- Tools and programs for unlocking public land exist, but a widespread answer will take input and attention from a diverse group of stakeholders with varied interests.

Access matters to onX—we believe that everyone should have access to nature. When people feel connected to the land, they are more likely to protect it. Read the onX Corner-Locked Report below to gain an understanding of the issue and what’s being done to address this complex problem.

The information provided here does not, and is not intended to, constitute legal advice, and may not constitute the most up-to-date information. Links to third-party websites are intended for the convenience of the reader and do not endorse third-party information.

The Crux of the Issue

In October 2021, four hunters were cited for criminal trespass in Wyoming. They had not entered a private building, nor had they touched private land.

What they had done was place an A-frame ladder across an intersection of property boundaries, the location where four parcels of land meet at a point. They climbed up one side of the ladder from public land, and down the other side of the ladder, stepping kitty-corner onto a different parcel of public land. But in doing so, their bodies also crossed through the airspace of the other two parcels meeting at that point, which were private. Their trial, set for mid-April, will decide if they trespassed when they passed through that private airspace.

Why Corner-Locked Lands Exist

The location on which these hunters set their ladder is not unique in the West. Most of the land in the Western U.S. is mapped and platted based on square, 640-acre sections arranged in neat rows and columns, a system known as the Public Land Survey System. As a rule, squares have four 90-degree angles. This means a hallmark of this system is four tracts of land meeting at a single corner point. As land was doled out to homesteaders and the newly formed states, designated for parks and forests and reservations, and retained or reclaimed by the federal government, a complex patchwork of ownership formed. Properties combined, split, and transformed into every imaginable shape, but the underlying unit—the humble, square, 640-acre section—can still be found all over the West.

With

Without

In many parts of the West, land ownership boundaries are invisible on the landscape.

Quantifying the Immense Scale of Landlocked Public Land

Within this patchwork lie parcels of public land that are landlocked, that is, surrounded by private land with no public roads or trails to access them. Since at least the 1970s, the hunting community has been well aware of inaccessible parcels, and many hunters have found particular locations with maps and binoculars that they can’t access. But nobody, including the federal land management agencies themselves, knew exactly how much public land was out of reach to the public. So in 2018 and 2019, onX and the Theodore Roosevelt Conservation Partnership worked together to discover 15.8 million acres of landlocked federal and state land throughout the West.

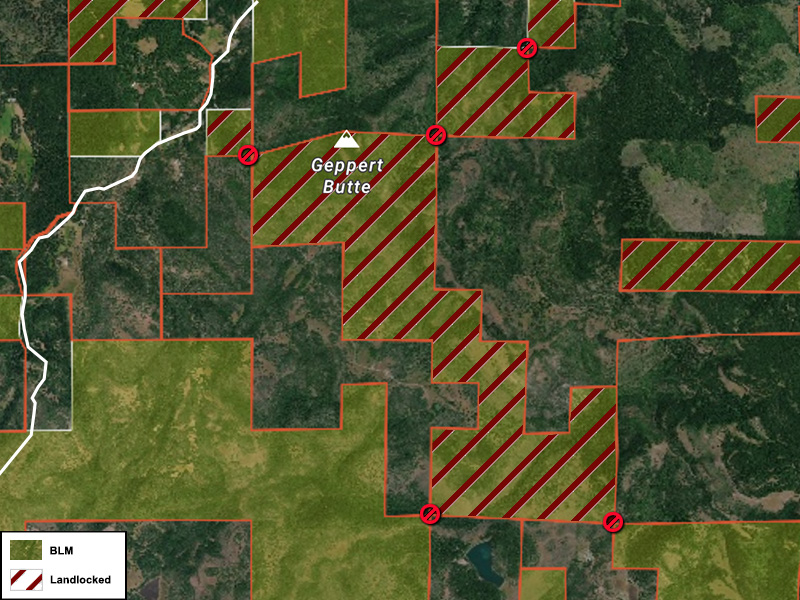

When we conducted that analysis, we noticed landlocked parcels fall into one of two categories, which we now call “isolated” and “corner-locked.” Isolated parcels are fairly self-explanatory: they are parcels of public land off by themselves, like islands in a sea of private land. Corner-locked parcels, on the other hand, are those that are mostly surrounded by private land, but do touch another parcel of public land at one or more corners.

![]()

Corner-Locked:

Public land that is inaccessible to the general public because there is no public road or trail to get there AND because the legality of corner-crossing remains unclear

![]()

Most hunters in the Western U.S. refrain from stepping over a property corner from one parcel of public land to another. Doing so is referred to as corner-hopping, corner-crossing, or corner-trespassing, depending on who you ask. Outside of the world of hunting, and outside of the West, this limitation is rarely discussed. In fact, there’s no law on the books that specifically states that stepping over a property corner from public land to public land is illegal. Despite various attempts to make corner-crossing legal or illegal by state legislatures, no state has yet passed such a bill into law. This has left the decision to prosecute “corner-hoppers” in the hands of local law enforcement and local courts.

At onX, we believe that publicly accessible land plays a critical role in equalizing everyone’s access to outdoor recreation, but we also recognize private property rights. Like we did with the landlocked analysis, we wanted to quantify the issue of corner-crossing. How much land is involved? How many property owners does it affect? To get the answers, we dove back into the data.

This report on corner-locked public land reveals a complex dichotomy and history between outdoor enthusiasts and private landowners. While some favor public access and others are looking to protect private property rights, several court cases and failed legislation have effectively positioned corner-crossing in a “legal gray area.” But there are programs and tools that simultaneously benefit landowners and the public, so we conclude the report with ways that public lands are being successfully unlocked—even without a definitive policy on corner-crossing.

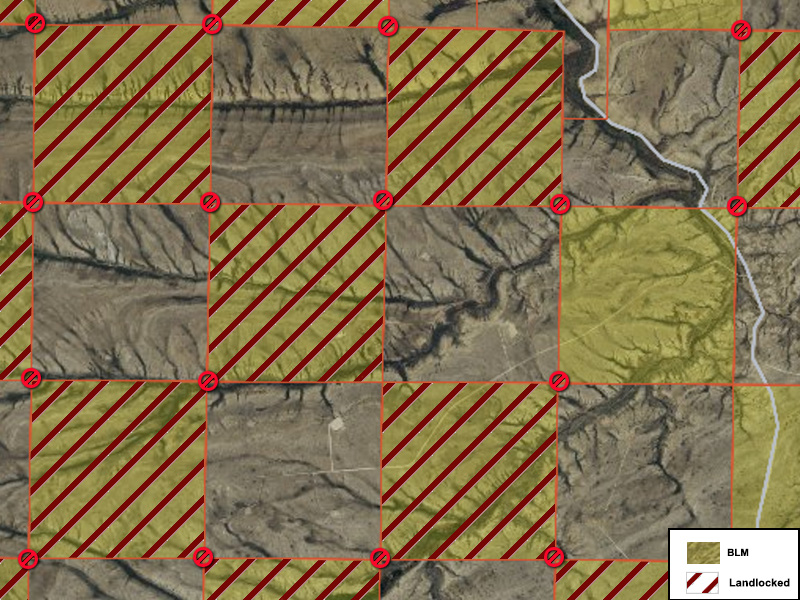

Corner-Locked: By The Numbers

Corner-Locked Acres

Over the past two centuries, legislation, random chance, and a variety of land deals have resulted in 27,120 property corners in the West where two parcels of public land meet on opposite sides of a point, with private land adjacent, effectively in between them. Beyond these corners lie 8.3 million acres of federal and state land that are inaccessible to the general public because the legality of corner-crossing remains unclear. In other words, more than half of all the landlocked public land in the Western U.S. would be unlocked if corner-crossing was legalized. These acres are not only off-limits to hunting but also to fishing, hiking, wildlife watching, cross-country skiing, and all other forms of enjoying the outdoors.

![]()

Corner-by-Corner Acreage Breakdown

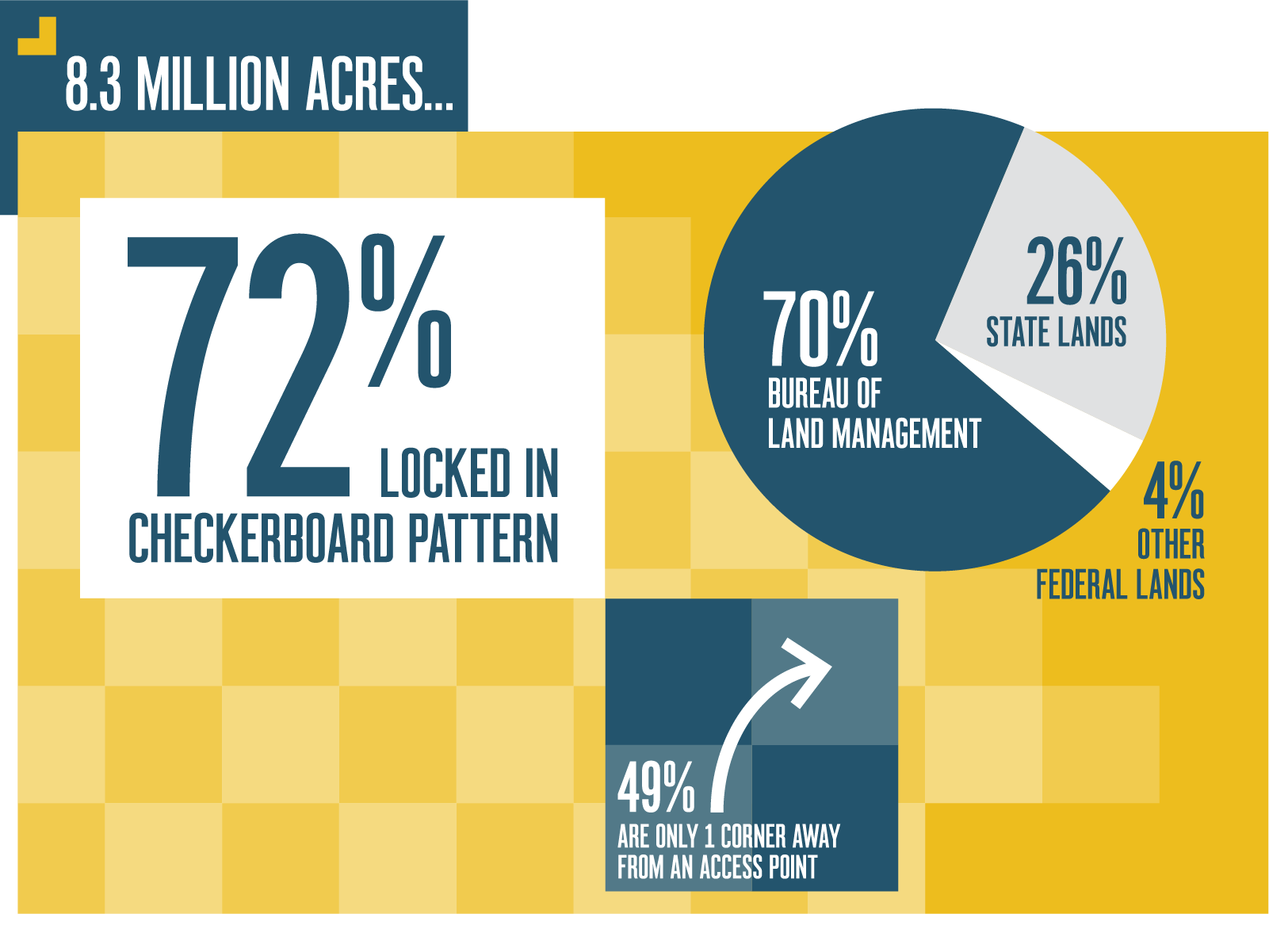

Of the 8.3 million acres, 72% (5.98 million acres) are locked in a checkerboard land ownership pattern devised in the 19th century to promote the Western expansion of the United States through land grants to railroad companies. The scheme did not go according to plan, so the alternating sections of ownership persist to this day. The other 28% of corner-locked public lands tend to be on the edges of larger units of public land, perhaps a result of land being bought, sold, and swapped over the past 170 years. Since the majority of the unclaimed and reclaimed land in the West ended up being folded into the agency that became the Bureau of Land Management, it’s unsurprising that 70% of all the corner-locked acres we identified are managed by that agency.

Looking at a broad swath of checkerboarded land stretching out for miles on either side of a railroad line, it would be easy to assume that much of the corner-locked land would be difficult to reach on foot, even if property corners didn’t stand in the way. But 49% of corner-locked acres are just one corner away from an accessible parcel. The remaining 51% would require between two and 15 corner-hops, if it could be done legally.

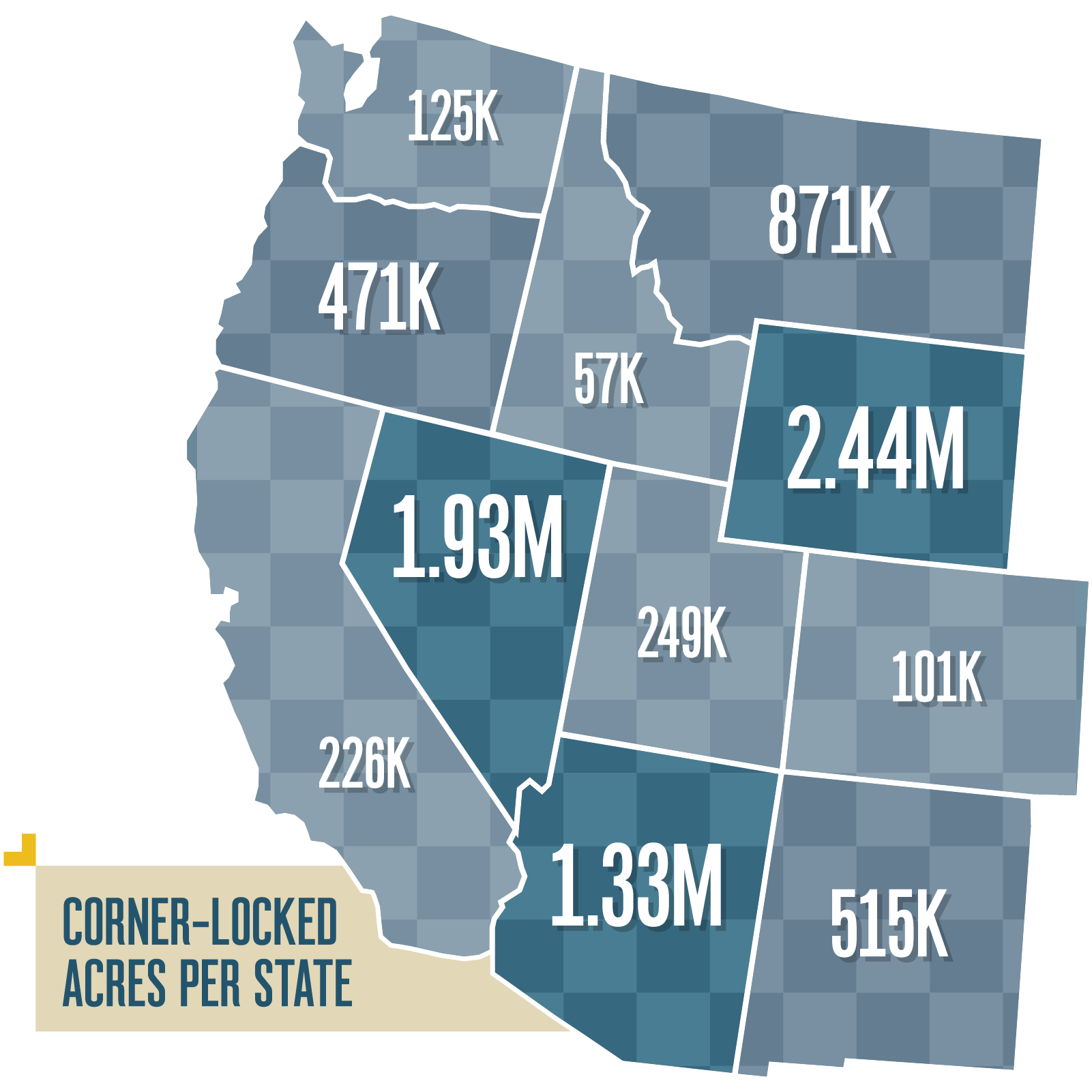

Corner-Locked Acres by State

The number of corner-locked acres varies greatly from state to state. On the low end, Idaho has 57,000 acres. At the opposite extreme, Wyoming has 2.44 million acres, thanks to the stretch of the largest railroad grant in history sweeping the width of the state from east to west. Nevada has 1.93 million corner-locked acres, Arizona has 1.33 million acres, and Montana has 871,000 acres.

![]()

Adjacent Private Land

Finally, we wanted to get a better understanding of the private land that is adjacent to corner-locked public land. The 8.3 million acres share a property corner with 11,000 unique, private, land-owning entities (both people and companies). Of the 27,120 corners that separate two parcels of public land, at least 19% are shared by land owned by an oil, gas, energy, timber, or mining company—not a rancher or farmer.

Landowner Views on Corner-Crossing

There are many reasons that private landowners want corner-crossing to remain off-limits, but we’ll cover just two common concerns here.

![]()

Concern #1: Airspace

One of the key factors in understanding why stepping over a corner, even without stepping a toe on private land, can be considered trespassing is due to a spatial concept of real property. Because land wouldn’t be very useful if ownership rights were limited to the surface—say, the level that worms and ants care about—there’s an understanding that the air space up to a certain height is also owned by the landowner. This understanding facilitates the building of structures and fences and has been used to ensure helicopters and drones can’t hover uninvited over someone’s house. Furthermore, property corners are thought to be infinitely small points in space. To step over a corner where two public land parcels and two private land parcels meet would therefore automatically put a person in the airspace of the private land, since we cannot shrink our bodies to be infinitely small.

All of this might beg the next question: why do some landowners care about the airspace of their property corners? In theory, hikers, hunters, and other foot-traveling public land users would occupy private airspace for mere seconds if they stepped over a corner pin then continued deeper into public land.

According to the website of United Property Owners of Montana, “To cross a corner, a member of the public must cross all four corners, including the private ones. That is a trespass—a physical occupation of private property.” Therefore, they say, “There is no ‘minimal’ amount of trespass that wouldn’t be considered taking of property.” This view has roots in the Fifth Amendment: “nor shall private property be taken for public use, without just compensation.” Essentially, landowners holding this view believe that no matter how small the space or how limited the time it takes to step over a corner, if the government were to allow the public to step from one corner of public land to another over private property corners, that would be a taking of private property and a violation of Fifth Amendment rights. To date, a court has yet to determine that a person stepping over a corner does or does not trespass on a private landowner’s airspace.

Concern #2: Bad Apples

Other landowners are more concerned with people who already blatantly trespass. One rancher in rural, southeastern Montana who has property next to public land put it this way: “If you had an individual that was trying to corner-cross legitimately, and they had their map with them, they should be able to do it, but I think the problem has more to do with human nature. When nobody’s looking, people tend to do what they want to do. In my area, hunters don’t have any reason to be concerned because they don’t think anybody’s out here or anybody cares. There are people who are totally respectful, but some bad apples really ruin it for the other people.”

This rancher, who wants to remain anonymous, sees trucks driving around in his pastures, sometimes well after dusk. Every rifle season, a fleet of trucks is parked on his private driveway. He’s witnessed people shooting deer on his property from the adjacent public land, and he’s caught people shooting deer well within his property. He’s heard shots ring out from the same direction as where his kids are out fixing fences, causing panic. There have been times he’s tried to approach trespassers and they’ve fled the scene, leaving dead or wounded deer behind. Law enforcement in his area is stretched too thin to respond to all the calls.

“When you already can’t trust people, it’s hard to think that corner-crossing would go any differently. If we could get enforcement under control, then it’d be a lot easier to talk about trying to open up more public access. It’s such a bad situation that the public ground and the private ground are mixed in this format of checkerboard. I know that there’s vast amounts of acres that would be opened up if corner-crossing was legalized. If the idea was that it would somehow spread people out more, that would be a good thing. But we need to get enforcement under control.”

A Confusing Legal Backstory

Though checkerboards of public and private land were born in the Western U.S. beginning in the 1860s, the matter of public access via corners remains unresolved. In recent decades, several bills and court cases seemed primed to resolve the question once and for all, but so far, none have successfully made it into law.

Wyoming, having the most corner-locked acres, is also the state with the most action on the topic. In September 2003, a Wyoming hunter was charged with trespassing after he stepped over a property corner pin from one public land section to another after locating the pin with the help of a GPS device. He had not received permission to enter the adjacent private land from the landowner or property manager. Ultimately, the hunter was not found guilty because he had not entered the property—or its airspace—to hunt, fish, or trap “upon the private property” but instead sought to hunt on public land.

The following year, the Office of the Attorney General of Wyoming issued an opinion that declared that the hunter’s trial had “no binding effect on any court” (that is, it did not establish case law). The opinion examined the difference between two different state statutes. One statute says a person cannot enter a private property with the intention to hunt, trap, or fish on private property without permission—this was the key phrase that acquitted the hunter. The other statute states a person is guilty of criminal trespass if the person “enters or remains on or in the land or premises of another person, knowing he is not authorized to do so…” The common dictionary definition of the word “enter” is even addressed in the official document. Ultimately, the Wyoming Attorney General at that time concluded that in any corner-crossing trial, “the factual circumstances would have to be examined” to determine if a violation of state statute had occurred. In other words, everything and nothing was clarified.

Not long after the Wyoming Attorney General’s opinion was issued, Wyoming Game and Fish Department (WGFD) sent a memo to law enforcement, wildlife supervisors, and the Wyoming Department of Agriculture which stated, “Simply crossing the corner of private property to reach public lands does not fulfill [the] requirement” to be convicted of the Wyoming Statute which makes it illegal to hunt on private property without permission. That seems like a win for access, but then the memo also states, “Unfortunately, that leaves the Game and Fish in the position of referring reports of “corner-crossing” to the local sheriff’s or county attorney’s office.” Finally, the memo warns, “…hunters may have the idea that it is now legal to cross section corners to access previously inaccessible public lands.”

Scratching your head yet? There’s more.

In 2011, a bill was introduced to the Wyoming House of Representatives which would have allowed entering one parcel of public land from another parcel of public land, as long as someone doesn’t physically touch private land or improvements on private land (things like fences) while doing so. Presumably, this meant that as long as two parcels of public land were a mere step apart, that step would be allowed. However, that bill did not make it beyond the committee hearing. In Montana two years later, a similar bill passed in the State Senate but failed in the House. Yet another similar bill was introduced in the Nevada Assembly in 2017, but, cryptically, “no further action [was] allowed.” And that was that.

Also in 2017, another Montana bill about corner-crossing was introduced. But this time, it was to make corner-crossing a misdemeanor punishable with a fine of $50 to $500 and up to six months of jail time. That bill, too, did not get passed by the House.

Following these bills are the cases of Cody Cherry, a Montana man who was charged with trespassing twice after repeatedly stepping over corners of the same ranch. The first set of charges were dismissed. In his second case, he was found guilty because, significantly, the corner of public land he was stepping to did not actually touch the corner of public land he was stepping from, due to where the boundaries were established in the 19th century…using 19th century surveying techniques. This meant he walked across about 80 feet of private property between public parcel corners. Clearly, the second time around he stretched the definition of a corner too far.

So to recap: two hunters in different states were both found not guilty after stepping over property corners, an attorney general opinion declared individual circumstances of corner-crossing must be examined, three states saw the introduction of bills to make corner-crossing legal, and one of those states also saw the introduction of a bill to make it illegal, but none of the bills became law. No wonder the debate rages on.

Mutually Beneficial Solutions At Work

The corner-crossing debate may very well continue throughout the rest of our lifetimes, but there are some bright spots on the map as various programs and tools are employed in specific locations.

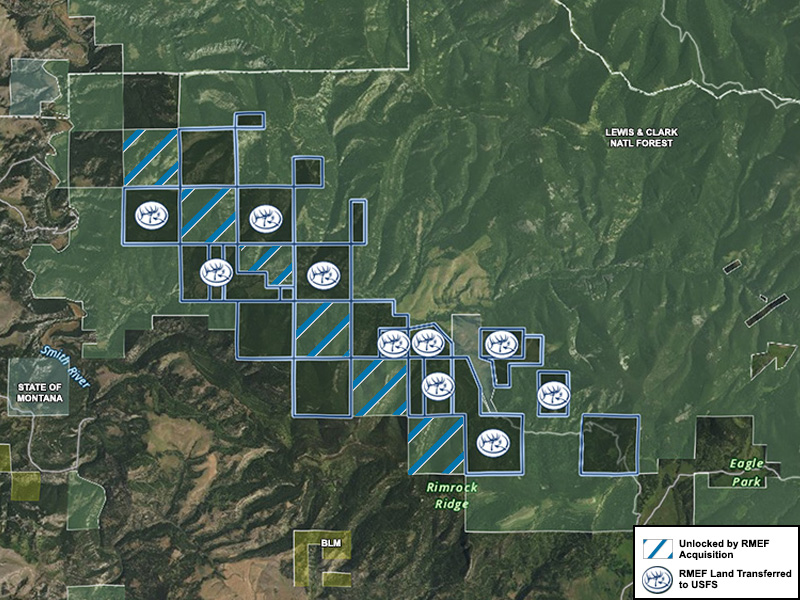

![]()

Navigating and managing checkerboarded land is hard for everyone—ranchers, timber companies, energy companies, hunters, outdoor recreators, and even land management agency personnel—so “un-checkerboarding” the land ownership through land swaps can be mutually beneficial. Private landowners get a tract of land that is either adjacent to land they already own or is in some way more attractive to them in exchange for property that they hold which is intermixed with public land. In other cases, outright sales of private land to a land management agency or an intermediary non-profit organization can fill in the spaces between parcels of public land.

These transactions can be expensive, but thankfully the new version of the Land and Water Conservation Fund requires at least $15 million annually be set aside for projects that improve public recreational access, and in fiscal year 2021, $67.5 million was appropriated for recreational access acquisitions. For example, in 2021, the Bureau of Land Management allocated funds to five projects in the West which secured or enhanced public access in the North Platte River Special Recreation Management Area in Wyoming, the John Day National Wild and Scenic River and the Table Rocks Special Recreation Management Area in Oregon, the Mojave Trails National Monument in California, and the Organ Mountains-Desert Peaks National Monument in New Mexico.

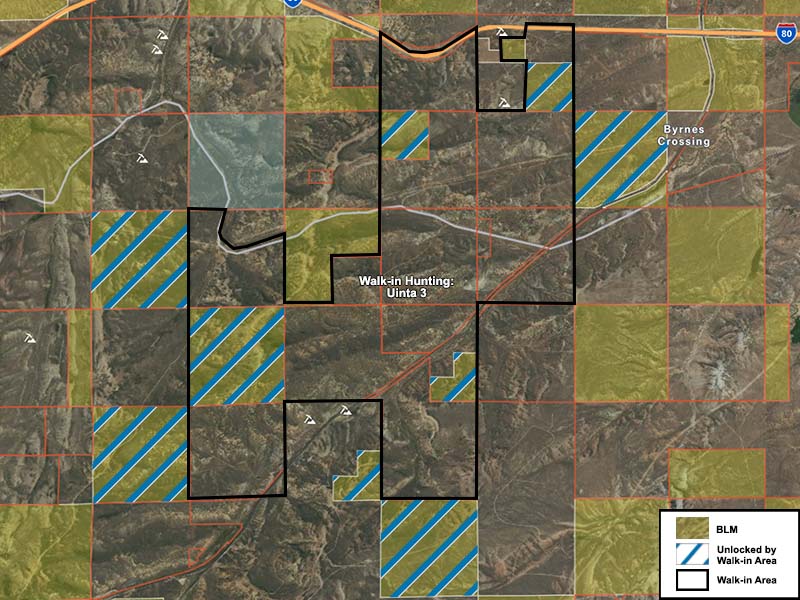

Another model to look to is the variety of state programs that provide a financial benefit for private landowners that open their borders for hunting access. Eight of the thirteen Western states have programs like this, including the Block Management program in Montana, Access Yes in Idaho and Wyoming, and Open Gates in New Mexico. In Montana, 618,330 acres of landlocked state and federal land were “unlocked” during the 2020 hunting season thanks to the properties enrolled as Block Management Areas. In Washington, 28,515 acres of public land were unlocked in 2019 thanks to landowners participating in Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife access programs. These programs provide an immense benefit, but as an alternative means of accessing checkerboarded public lands, there are some limitations. In most cases, these programs only apply to hunters, only for a short period of the year, and not all participating properties are adjacent to landlocked public lands. Furthermore, these agreements with individual landowners are established on a year-to-year basis, leaving uncertainty about long-term access, as landowners can change their minds about participating in the program or can sell their properties.

One state-run program, the Unlocking Public Lands program in Montana, provides an annual tax credit to landowners who provide access across their property to “locked” public land for hiking, birdwatching, fishing, hunting, and trapping. A fact sheet from Montana Fish, Wildlife & Parks specifies that “landowners could also be considered for an agreement if they own land adjacent to the point where the corners of two parcels of public land meet.”

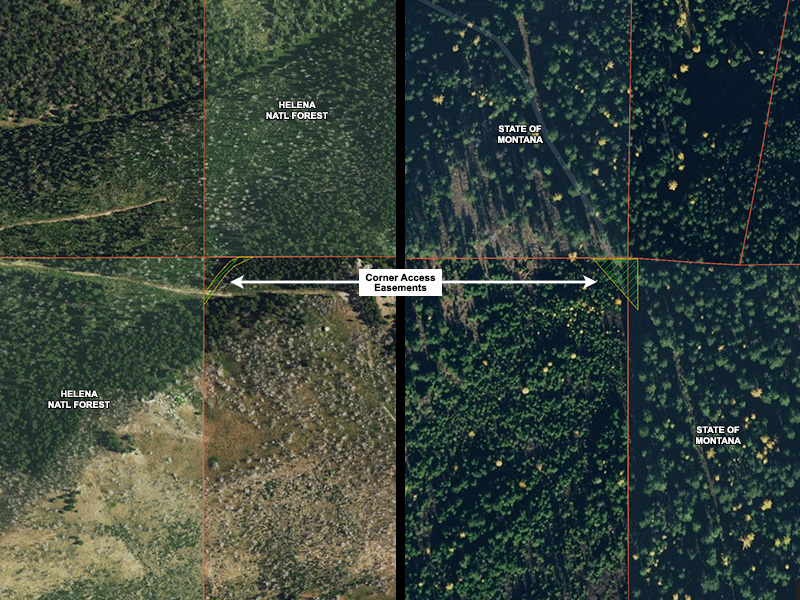

Corner easements could be another viable option in specific locations. Easements are the legal right to use another’s property for a specific purpose. Access and right-of-way easements specifically grant the holder the right to travel through another’s property. Many government agency-held easements grant the general public the right to use them. Oftentimes, these types of easements are created during the process of a land sale or land swap, but they could also be purchased by a land management agency or conservation partner without a change in land ownership. In places where the easement crosses or skirts around a property corner, the easement needs only to be a few feet wide and a few feet long. The advantages of this solution are that easements last in perpetuity, even if the land is sold, and the narrow path of the easement means that members of the public have to stick to the designated route—they cannot wander onto the rest of the private land.

Lastly, there’s one more tried-and-true way for the public to gain access to corner-locked land: by asking the neighboring landowner for permission. It may not work everywhere, or every time, or with every landowner. But there’s a history in the West of knowing one’s neighbors. As the population of these once-rural places grow, earning and building relationships with landowners may be the least expensive way to gain access to inaccessible public land.

“Last year, a couple of dads from Missoula and their sons showed up and asked me if they could hunt here. I told them to give me 15 minutes and I’d take them out with me. We got some really nice mule deer bucks for their sons, and they helped me work cattle the next day. We got some antelope for the dads the day after. So we had fun. One of them even bought beef from me this year.”

Eastern Montana rancher

What’s Next?

The basis of platting land in squares was meant to make keeping track of landownership easy, but it has come with unforeseen consequences. One of those consequences is that now, millions of acres of public land are considered to be off-limits.

![]()

The patchwork and checkerboards prevalent in the West impact everyone: landowners, hunters, federal land managers, and anyone who likes to ramble the countryside. It’s hard to navigate, and it’s hard to manage; after all, mountains, rivers, lakes, and hills do not care about the squares we humans draw on maps.

The hunters who used a ladder to corner-cross in Wyoming now face a civil lawsuit from the owner of the private land whose airspace they stepped through, in addition to the original criminal trespass charge. Their criminal case, currently set for April 14th, will take place in a local court and therefore will not establish legal precedent. However, on March 31st, a judge ordered for their civil case (that is, the one brought by the landowner) to be moved to federal district court, where the outcome could serve as precedent in future cases. Whatever comes next, this legal gray area could very well remain clear as fog for decades to come.

Knowing where you stand is critical.

Create a free onX account today to access property line maps.