Opening weekend of deer season in the Wisconsin Northwoods is a lesson in tradition. Just ask the decades-old local businesses that still bear witness to it.

The first thing you should know about Big Dick’s Buckhorn Inn in Spooner, Wisconsin, is that only two of the mounts on the wall are fake.

The sabertooth tiger and the jackalope are imposters. All the others—elk, black bears, bison, moose, hogs, a two-headed red angus calf, and scores upon scores of whitetails in every antler configuration imaginable—are quite real.

The second thing you should know is that, in 1960, John F. Kennedy showed up to the Buckhorn during his presidential campaign.

“He drank a beer, used the bathroom, hugged two little girls, then walked out,” bartender Sherman recalls, pointing out the framed newspaper articles documenting the event that hang next to the bathroom door. This moment in history is a point of pride for the establishment, along with its age (121 years old), its front and back bars (both original), and its pair of phallic shotskis (true to the name).

The Buckhorn wasn’t very lively on the Friday morning before the opening weekend of Wisconsin’s deer gun season. Not at first, at least. But before long, two guys came in. Then came another six. Then two more, and four more after that. In the space of 15 minutes, Sherman’s morning went from quiet to busy—and not busy with just anyone strolling down main street Spooner, but busy with patrons in various combinations of camo and blaze orange, drinking Leinenkugels and fretting over tree stands, food plots, cabin logistics, and the rut being basically over.

This was the classic precursor to the nine-day deer season, a stretch on the Wisconsin calendar that can be likened to a lot of things: a religious holiday, a cult gathering, a woodland requiem, a trip to the outdoor grocery store. Most consider it a tradition that has faded with time. When asked about the state of Wisconsin deer hunting culture and places like the Buckhorn that make it special, the rank and file respond universally with a raised eyebrow, a head tilt, and a slackening of the face.

“It ain’t what it used to be.”

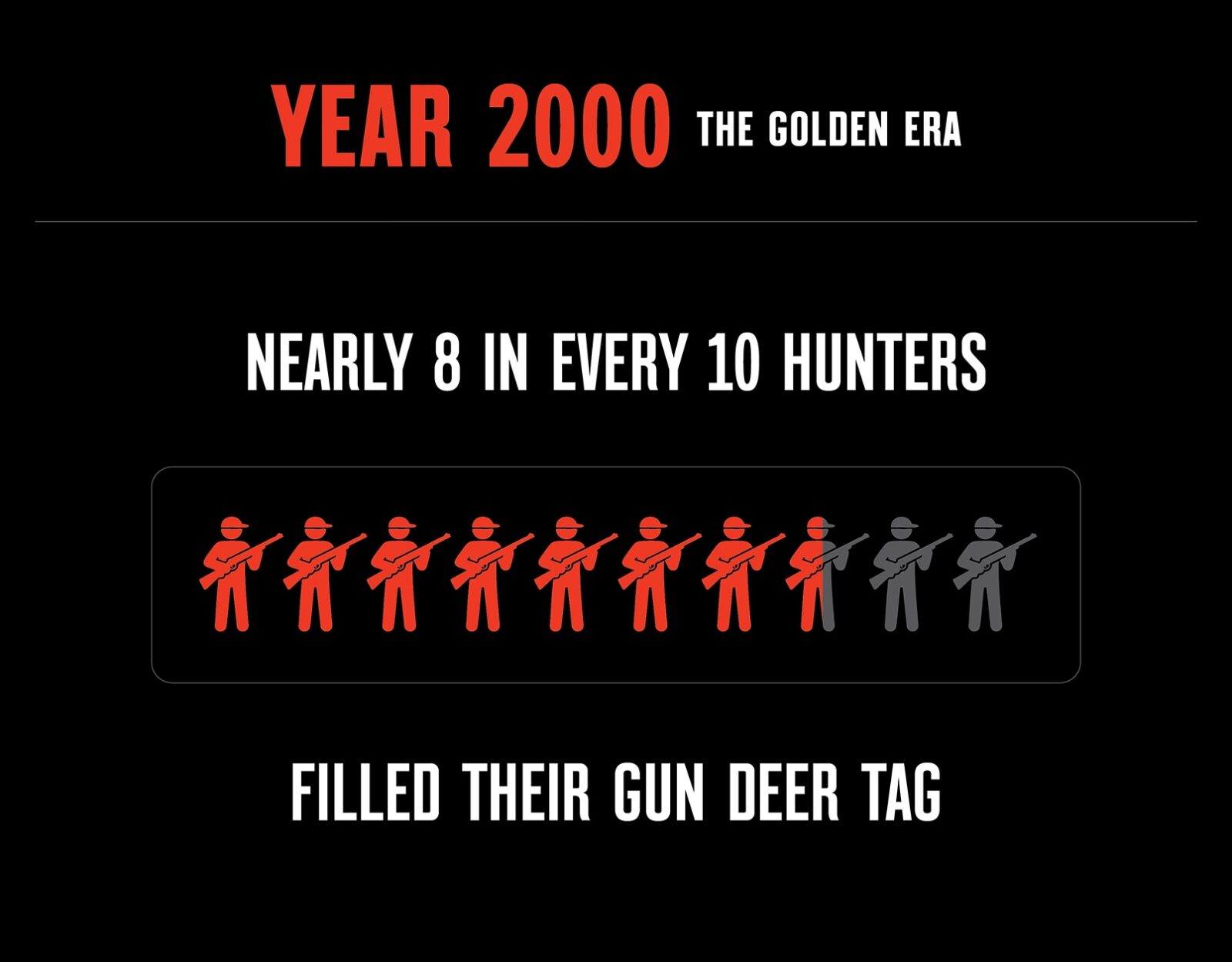

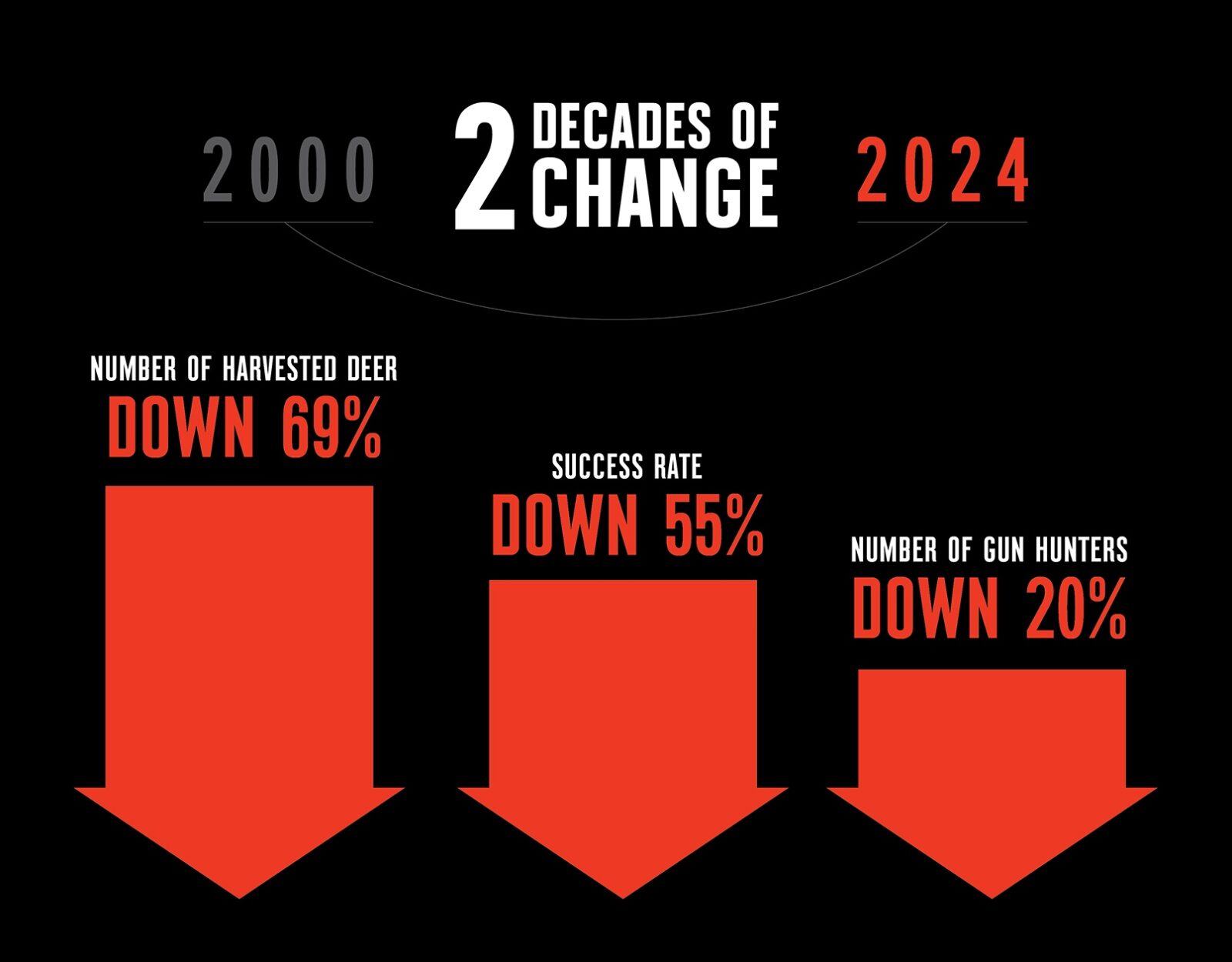

Business may be booming at the Buckhorn—Sherman has the all-time sales record from July of this year to prove it—but after hitting a peak in 2000, Wisconsin deer hunting participation has faced a steady decline. In the Northwoods, especially, deer harvest has followed suit. Some hunters blame wolves. Others blame poor habitat. Others still blame each other. Whatever the answer is, statewide post-season deer counts reached a record high in 2024, a data point that befuddles the same frustrated hunters into a silent sip of their beer and a change of the subject.

And yet, there they are in the Buckhorn, spending their dollars in a bar that’s been serving proactively frustrated deer hunters since its advent. As long as whitetail deer still tread Badger State soil, hundreds of thousands of hunters still emerge from their normal lives to hunt those deer for some combination of nine days in November. At a time when big box stores, online shopping, and an overall retreat from community spaces plague the nation, the hunters that remain dedicated to Wisconsin’s deer season—and their wallets, appetites, empty fuel tanks, and non-negotiable need for a few hours of sleep in relative comfort—might matter more to Main Street than ever before.

When big box stores, online shopping, and an overall retreat from community spaces plague the nation, the hunters that remain dedicated to Wisconsin’s deer season might matter more to Main Street than ever before.

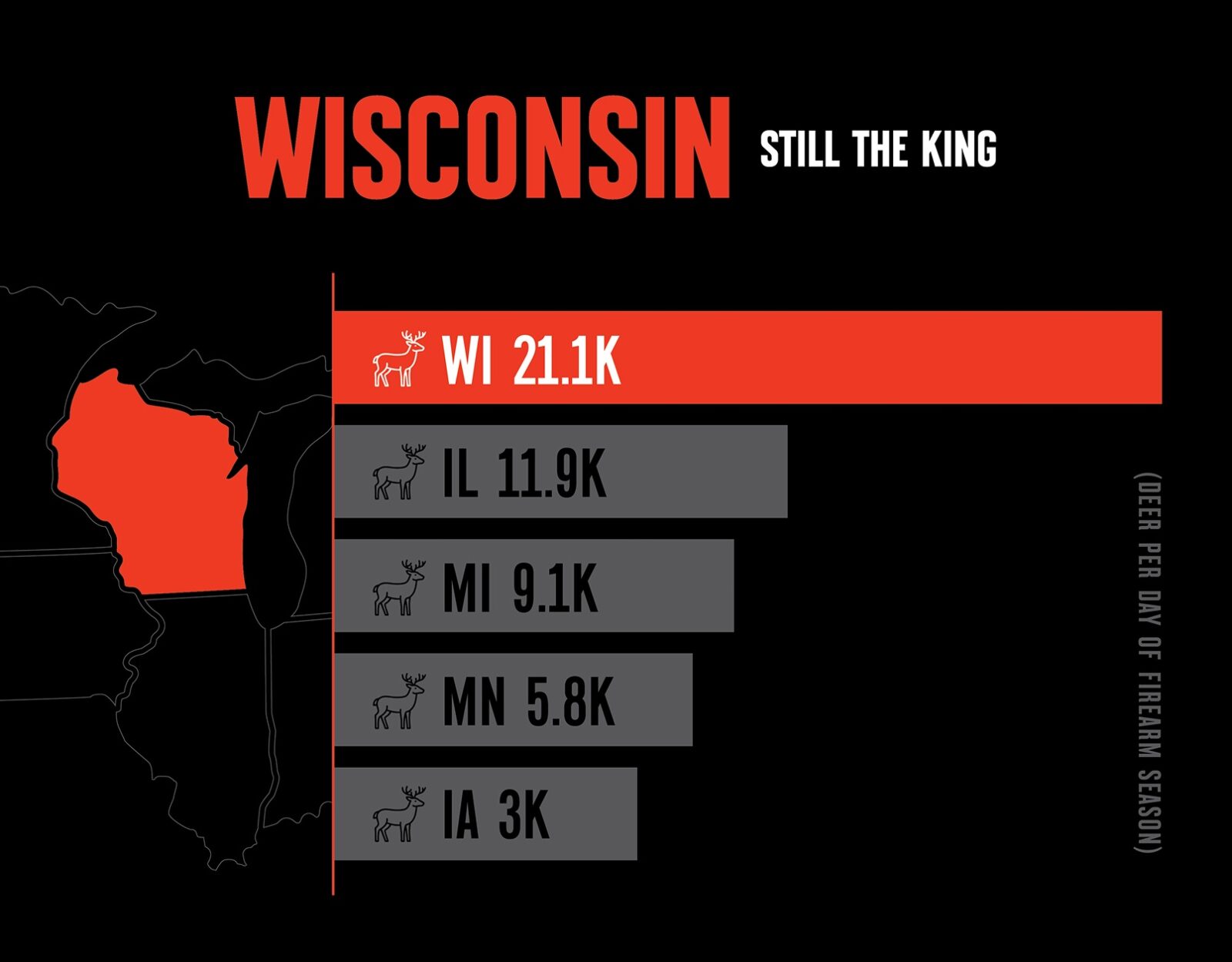

No state has consistently exalted in deer hunting for over a century quite like Wisconsin. The gun season is especially short and harvest is high. Accordingly, it receives holiday treatment in many households and communities, and not just because it overlays Thanksgiving. Public schools in the town of Hayward, for example, are closed Monday, Tuesday, and Wednesday before Turkey Day. Old wives’ tales about statewide hunting season school closures “back in the day” circulate comment threads in nostalgic Facebook groups.

The mania isn’t limited to Wisconsinites, either. Nonresident hunters show up in droves. For the whitetail enthusiast, Wisconsin is nothing short of a bucket-list destination. The Boone & Crockett Club lists it as the top state in the nation for record whitetails, with 1,960 total book entries by Field & Stream editor Scott Bestul’s recent count and six of the top 20 record-producing counties in the U.S., including number-one Buffalo County.

Wisconsin: Two Decades of Change

Accordingly, the tourism boom that comes with such a huge influx of people is worth investigating as a feat of outdoor economics in its own right. The hunting community is pretty good at talking about the financial benefits of their favorite fall pastime, specifically the story of the Pittman-Robertson Act that’s quick on the lips of any hunter in conversation with someone who has yet to drink the camouflage Kool-Aid. That story is good and important, but it’s also far from the only financial benefit of hunting. Hunters patronize hotels, motels, lodges, campsites, restaurants, bars, cafes, diners, liquor stores, grocery stores, butcher shops, delis, sporting goods stores, souvenir shops, convenience stores, gas stations, gunsmiths, auto mechanics, drug stores, taxidermists, airports, the list goes on. Hunters spend an estimated $2.6 billion in Wisconsin every year.

Regions like the Northwoods, where year-round populations are small and local economies revolve around outdoor tourism, rely on hunting season to build an economic bridge between uber-busy summers of paddling, biking, and fishing traffic and winters of snowmobiling, cross-country skiing, and, well, more fishing traffic. That’s certainly the case for Mike Bilodeau, owner and manager of Chetek Rod and Gun.

“I do 80% of my business between Memorial Day and Labor Day,” Bilodeau says. “Then it slows down a little bit in the early fall, and then gun season is the kick. There’s people coming through the door all the time…I was just going to make a sign about my ‘holiday’ hours.”

In 2010, Bilodeau and his wife became the third family to operate the business since its inception in 1949. Walking inside under the monstrous bass sculpture mounted to the storefront, even a first-timer can tell that little has changed in 76 years. A DNR map of the state’s hunting regions anoints the glass case under the cash register. The back room boasts everything a hunter needs and nothing they don’t; new and used guns priced accessibly, various brands and iterations of ammunition, optics, carrying cases, blaze apparel, a few bags of food plot seed, mineral licks, and deer feed (this is Wisconsin, after all).

While Bilodeau visits with a customer and organizes his stock of ammunition behind the back gun counter, customers at the front counter purchase hunting licenses and chew the fat with other employees, discussing plans for the weekend and joking about unfruitful archery seasons during which they tried—and failed—to compete with swarms of does for the attention of rutty bucks. The warmth of community radiated through the store, a secondary service Bilodeau provides for the town of under 2,200 people.

“My goal was not to screw it up when I bought it,” Bilodeau says of the store’s positive reputation in the community. “There aren’t a lot of small sports shops around anymore, but Chetek is small enough to not have any big box stores. All the other towns around here have those stores, and it’s tough to compete with them.”

If Chetek Rod and Gun warms the heart, Lynn’s Custom Meats and Catering in Hayward warms the stomach. Owner Lynn Melton builds business off of the annual hunting boom twofold; by feeding hungry hunters with her mouthwatering assortment of marinated meat, fish, snacks, and deli offerings, and then turning the trim venison from the deer they eventually harvest into any of the three dozen specialty sausage, snack stick, or bacon recipes she boasts. Her favorite?

“The medium garlic summer sausage would be my number one choice,” Melton says. “The teriyaki sticks are very good, especially the pineapple teriyaki. We have a new apple cheddar snack stick, which reminds me of fall because it has that nutmeg and cinnamon flavor. Our mac ‘n cheese brats and our Philly cheese brats are very popular, too.”

After 17 years in the deli and butchering business, Lynn’s is a resounding success. One hunting customer follows Melton around the store, so excited about a future custom sausage order that Melton gently reminds him that he must actually kill a deer before he can place an order with her.

“It’s a lot of fun to see the hunters come at this time of year,” she says. “In the old days, business picked up a lot [during hunting season]. Nowadays, not as much, but it’s still busier [than the rest of the year]. You still have the diehard hunters who love to do this.”

Like it does for Bilodeau’s sporting goods store, hunting season provides a nice boost for Melton’s butcher shop through the winter months, even though her staff doesn’t do the actual cutting. She sends customers to David Lee’s Custom Processing, who was busy enough on the evening of the opener to politely turn away any questions or subtle requests for a visit. When Lee is done with the processing work, a job Melton says he does with surgical precision, hunters bring the trim destined for a grinder back to her crew. That’s when they work their magic.

Hayward has a large grocery store, but Melton doesn’t worry much about the competition they might create. She’s confident in the following she has built in her community, as evidenced by a section of the back wall littered with service awards from the Chamber of Commerce and the local Lions Club.

“In the beginning, it was scary. There were a lot of sleepless nights wondering what I’m doing, doing this on my own,” Melton recalls. “But over the years, people have come to know what we put out and what we can do. I don’t want to brag, but I have a nice following of people who say ‘Oh, I know you,’ or ‘Hey, go to Lynn’s.’”

Opening morning in the Northwoods is quiet this year. State forester and lifelong Wisconsin deer hunter Ron Weber hears fewer than 10 shots from his spot near the small community of Cable, a far cry from three or four decades prior when the big woods would pop overhead like a New Year’s Eve party. The morning passed without a deer sighting, although a bobcat slinked by Weber’s ground blind, only his second bobcat sighting in decades of time spent outdoors.

Bobcats excite Weber. So do big mushrooms, birds, black bears, and all the other sources of free entertainment the Northwoods has to offer. Fewer people seem to seek that entertainment these days than in past decades. But Cable was anything but a ghost town on the day before the opener.

“Sure, there are less cars going to the gas station, and less people buying food from Rondo’s,” Weber says. “But I went there yesterday, and there were 10 other people there. You could tell they were all deer hunters.”

Weber is something of a Wisconsin deer hunting historian. He regularly delivers a presentation about that history at local community centers and private events. The concluding slide features three photos. The first, black-and-white from a deer camp in the early 20th century, shows a buck pole laden with a lineup of deer. The second, in color from Weber’s own family deer camp in the 80s, has fewer deer but more happy people. The third photo, the most recent, shows a mother, father, and young son gripping a single buck by the antlers. The caption on the slide reads “The good old days.” As in, maybe these are the good old days.

The slide features three photos. The first, black-and-white from a deer camp in the early 20th century, shows a buck pole laden with deer. The second, in color from Weber’s own family deer camp in the 80s, has fewer deer but more happy people. The third photo, the most recent, shows a mother, father, and young son gripping a single buck by the antlers. The caption reads “The good old days.” As in, maybe these are the good old days.

The first day of the opener comes and goes. Back in Hayward, after shooting light has long since faded, Dan Snider pours drinks for blaze-robed Badgers fans watching the game at Angler’s Bar and Grill, where Snider’s a manager. He confirms that, yes, really, his kids have the week off from school for hunting season.

“It used to be that you could go to your teachers and say you were hunting,” Snider recalls. “If you were, say, a freshman in high school, you could say you were hunting with your parents and your teachers would give you your assignments and you’d just have to do them. But now, they just don’t have school.”

A single glance around both rooms of the cavernous restaurant explains why; over half of the patrons at the crowded tables still wear their blaze orange, many of them school-aged kids—kids who, one day, might remember their early years hunting with family and eating at Angler’s after last light as “the good old days.”

The Badgers eventually pull off a miraculous upset against Illinois. Many of the parties pay their tabs and amble for the door. One older hunter stops short of the exit and shouts over the din to a familiar face, still seated at the bar.

“Hey, bud! You see anything today?”

His friend shakes his head slowly, elbows propped up on the bar to cradle a weary face. “Nothing.”

“Oh, that’s alright,” his friend replies, waving news of the unsuccessful day off with one hand and grabbing the door handle with the other. As he pushes out into the cold night, he turns over his shoulder once more.

“That’s what tomorrow’s for.”

Original article by Katie Hill, freelance environmental journalist and outdoor writer.